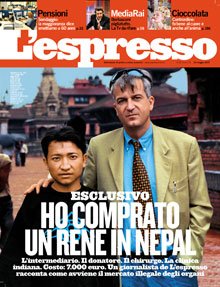

I have bought a kidney in Nepal by Alessandro Gilioli from Kathmandu

You can say anything about Krishna, a crook on the rise, except that he doesn't know how to sell his merchandise. "My donors are sturdy, healthy kids from the country. For me they've got to be in shape: no smoking, no drugs, no alcohol. And then I always do all the tests: HIV, hepatitis, TB. When it's over we pick the best, and you take them away. It's easy; we've already done it dozens of times with people from Europe, America and Singapore...".

So it isn't a metropolitan legend: the international butchery of human organs is a concrete, flourishing and widespread reality. Which now also has specific faces, names and addresses in at least one of its many incarnations: kidney trafficking between Nepal and India, Asia's busiest countries along with Pakistan in this shady global market. L´espresso has tracked the entire route from the alleys of Katmandu to the lavish clinics of Kolkata, purchasing a Nepalese youngster's kidney and making an appointment for the transplant with the consent of an Indian surgeon.

At the forged documents bazaar.

It's precisely in the ex-hippie mecca of Katmandu, exhausted by ten years of civil war and overpopulated by uncontrolled urbanization, that in November 2006 I hear the first rumors of booming local organs market. They say refugee peasants, villagers in debt and widows without hope have become the reservoir of this trafficking handled by a dozen middlemen, intermediaries between wealthy patients (mostly foreigners) and aspiring organ peddlers. In the post-war confusion, state power is compromised, crime is on the rise, corruption is rampant. And in reply to Nepalese anarchy, just across the border in India's new and modern private clinics, surgeons paid by-the-case accept forged Nepalese certificates fully aware of their fraudulence.

In this context, at the end of April I return to Katmandu with a bogus diagnosis of bi-lateral polycystic kidney disease, ostensibly seeking a transplant to avoid undergoing dialysis. I also carry a couple of fake blood tests revealing creatiniemia levels off the charts and other anomalies along with a diagnosis of my condition written on paper bearing a physican's letterhead.

I darken the shadows under my eyes with mascara and visit the National Kidney Center, the city's best-known private clinic for kidney therapy. Here, without having to produce a thing, I soon discover that it's enough to leave your cellphone number and a tip with any paramedic, but even a guard or a porter will do, for the word to spread that a new kidney is urgently needed. No one's surprised, no one asks anything, many promise help.

Less than three days later, the first phone calls come in with the names, numbers and addresses of two intermediaries, and I begin my venture into Katmandu's underworld , upgraded from drug-pushing to the more remunerative traffic in human organs.

The first middleman to give me an appointment is Krishna Kanki, whose base is a pashmina store on Tridevi Marg, an avenue teeming with beggars just a stone's throw from the Thamel tourist district. For more security, I visit him with a Nepalese friend, Sudarshan, whose brother bought a kidney a year ago and therefore has some experience in the field. As we near the store, we see Krishna waiting for us. About 30, he has a well-trimmed mustache and wears a violet polo shirt. He nods to us to follow him and, without turning around, leads us to a small out-of-the-way square, Bhagwan Bahal, where a few plastic chairs under an umbrella in front of a shabby bar constitute his informal office. Without once looking at me, Krishna speaks only with Sudarshan, in low tones and in Nepalese. My health doesn't seem to interest him particularly, except for the blood group, and after his reassurances on the sturdiness of his donors he outlines the next phase to us.

In his opinion, it's all very simple and well tested: "As you know, Indian law requires that donor and patient be blood relatives. For patients from here we have some certificates prepared saying that they're siblings, while for Westerners the best system is to invent ourselves a child." A child? "Sure, of course. We say you came to Nepal twenty years ago and spent a night with a local girl. Fine, you didn't take the baby back home with you, but you always helped him from a distance, sending him money and clothes. So now he wants to repay you, and he gives you his kidney. It's easy, works every time. Just prepare a certificate of paternity stamped by the ministry ,which we obviously know how to obtain." But who would the mother be? "That's no problem; we find a woman about your age who certifies your old relationship and guarantees the boy's paternity."

Luminaries and mercenaries

The middleman's nonchalant description of the various steps is somehow unreal , as if I were there to buy a souvenir. In any case, before his galling confidence, I try to show the qualms and disbelief of the typical Western patient worried that something may go wrong : "But are the documents credible? And what if the Indian surgeon refuses them?" Without so much as a glance at me, Krishna smirks: "Look, nobody cares whether they're credible or not. Sure, we produce perfect counterfeits, but only for security. The fact is that the surgeons in India know perfectly well that all of it's bogus and they only pretend to believe us." Continuing, always with a touch of irony: "Sometimes they even call us themselves and tell us what to write on these documents, to avoid problems with their boards of directors or maybe some jealous colleague. Keep one thing well in mind: if the Indian doctor asks you too many questions, he only wants a surcharge in black on the clinic's bill that already brings him 50% on every operation.Give him a good tip, and don't worry: that'll be the end of it."

After awhile, Krishna even seems irritated by our anxious questions, almost as if they could cast doubt on his professionality and connections with physicians across the border, and in reply to my misgivings about the capabilities of Indian surgeons, our go-between calmly comes up with the first name: "I work with the best transplant surgeons in the country. In Chennai I send patients to the head of the St.Thomas Hospital nephrology ward, Dr Ravichandran. Outstanding, a world-class surgeon. He's already done several Westerners like you for me, and they've all gone back home happy and content."

Daniel Rai's fearful tremor

After half an hour of reassurances and small talk, the conversation inevitably touches on costs. And Krishna reels off his fees without embarassment: "Blood tests and at least 2 possible donors: 160,000 rupees (approx. 200 euro) down. Next, if all goes well, the kidney will be 1,800 euro: one third down, one third right after the operation and the last payment on discharge from the hospital." Other costs? "You owe nothing to the donor; that's my business. If you want to, buy him some clothes so he'll look decent when you introduce him to the doctor. Hospitalization in India and all medications are at your expense, of course. Next, factor in 3 flight tickets to Chennai: for you, your donor and my watchman." And who would this watchman be? "I always need someone to keep an eye on everything for me. If a donor suddenly decides to escape at the last minute, my watchman's there to stop him. At times these kids are strange, all at once they get scared. It's always better to keep an eye on them." At this point he stops, glances at his gold watch and then looks up: "While we're on the subject, do you want to meet a couple of them?" In this way, Krishna reveals his weapon by surprise: a number rapidly digited on the cellphone, a few curt phrases in Nepalese, and three minutes later two already recruited boys, walking slowly and in total silence, come into sight from behind the corner. "Naturally, we have to check the blood group first, " says the mediator, "but they'll be ready in advance."

One is hardly more than a child. He has Tibetan features and is shockingly thin under a filthy T-shirt. His left leg trembles and he stares fixedly at the table ,apparently terrified by the situation he himself has chosen to live through. Much calmer, other youngster has the beginnings of a beard on his chin and sits next to his butcher. They drink a Sprite without breaking their silence. I look into their faces; they stare at the asphalt under their plastic thongs.

A few minutes later it's Krishna himself who makes them say a few words, perhaps fearing they may seem rude to the rich European client. The smaller of them, the frightened one, begins. His name is Daniel Rai and he claims to be 20 : obviously a lie , he's probably under age. He comes from a small village in the Terai region ,a stifling plain along Nepal's southern border. He says his mother died when he was 8, after which his father found another woman and began to drink, creating debts for alcohol and finally abandoning the village with his new companion. Left alone, Rai, as the oldest son had to defend himself and his brothers from the creditors. The money scraped together with odd jobs since coming to Katmandu can't cover the 30% annual interest demanded by usurers and unless he quickly returns to the village and pays them, they'll take the house and throw his brothers into the street.

The larger boy, Sonam, says he's 25 and comes from the village of Kavre in Teral. His job as a mechanic's helper in Katmandu brings in about 40 euro a month, but his wife now has a heart condition and, as "medicine's expensive in Nepal, without my money she'll die."

When they've finished, Krishna grins ironically, giving us a knowing look: "They all tell tear-jerker stories, and then you never know what they really do with the money. I'm honest; I always give them half of what I get, but when they see all those rupees at once they go wild. Some take to drink, others buy themselves a big bike: a fancy Hero Honda to go back to the village with and show off. Then, sure, there are also the good ones, who maybe buy a field to grow rice on, but they're more or less two out of ten. Anyway, it's their business."

Yes, their business. The important thing for me is that they're truly willing to sell an organ. How can I know they consent to what we're about to do? Before my perplexities, Krishna turns to the boys and says something in Nepalese. Daniel answers with a simple affirmative nod, always staring at the ground; Sonam , perhaps a better actor , even says he's "happy" to be able to save my life.

All told, the first meeting with Krishna and his boys-to-butcher lasts almost an hour in a vaguely unreal atmosphere: Daniel Rai, Sudarshan and I apprehensive, Krishna and the other donor calm. Then Krishna dismisses the youngsters and gives us the final details: "If you accept, give me the money for the exams right now so that we can do them tomorrow morning. Then I'll prepare the documents, which will be ready in a few days. If everything's OK, you'll be in Chennai within a week and back home with a new kidney within a month." The 160,000 rupees change hands, Krishna slips them rapidly into his jeans' pocket without even counting them and makes an appointment for me the next day at the Pathology Laboratory clinic the Kalanki area, so I can verify that the boys really take their blood tests. This done, he jumps to his feet and disappears into the crowd of Thamel.

I won't see him again, because my sale will be handled through other channels. By this time, Daniel Rai's probably already sold his kidney to some other foreign patient. As for Sonam, who knows? My impression , shared by friend Sudarshan, is that he may merely be an accomplice of the middleman, brought in to fill space and give us the appearance of a choice, while the predestined victim seemed to be the other boy in any event.

The children buried in the garden

The appointment with the second agent takes place the next afternoon. Hari Tamang, 50, stocky physique and blue designer glasses, has a photocopy and fax store front in an alleyway of the Bagh Bazar business street. Inside, a lone photocopier, an outdated computer, a poster-sized photo of the late king Birendra and a fake wood table. Hari knows why I'm there, has me sit down and starts the conversation, mostly about himself: "Everybody here knows me; I'm the best in the city. I've had Canadian and German patients; my documents are always perfect. Today there's a boom in Nepal and everybody's suddenly become an intermediary, but you can't trust them. I've been in this work for ten years; I've sold a kidney myself, and so has my wife." Then he points to an adolescent wearing a turquoise earring who's listening to music at the adjoining desk : "And that's Prakash,my son: as soon as he's old enough we'll be sending him to India too."

His strong point, Hari boastfully relates, are his relationships with Indian surgeons, cultivated during a decade of corruption. Hari names Ravichandran at Chennai, the same doctor indicated by Krishna. Our intermediary adds that he also works with another private clinic at Chennai, the Medical Madras Hospital, where he tells us his reference is "the famous doctor Georgi Abraham." But in my case, he says, the best thing is to go for the Apollo Gleaneagles Hospital in Kolkata where he claims to knows everybody in the nephrology ward: "They did transplants on three Westerners there just last week," he explains, "and then, in this period West Bengala is the best place".

Up to a few months ago, he relates, his favorite base had been Madurai in Tamil Nadu: at the local Apollo Hospital he'd worked without problems with a certain doctor Palani another kidney transplant expert. But now the police have their attention on Madurai, and it's better to keep a distance." Why? Hari grimaces and explains that in Tamil Nadu , the Indian region worst hit by the 2004 tsunami , the sale of organs has exploded beyond all measure in the past two years because people needed money to rebuild their houses. The spare human parts market attained dimensions that finally forced even the lazy local police to move. This triggered a couple of investigations and now the doctors have to lay low for awhile.

For that matter, complains Hari, even in Delhi you can't work the way you used to: last December at Noida , an industrial center near the capital , they found the skeletons of eight children in the garden of a private home, and the judge suspects they were murdered in order to extract their saleable organs. The bodies were too badly messed up and had been buried for too long to tell whether the organs had been excised or not, but for the time being physicians in Dehli are biding their time and the kidney market's practically at a standstill. Instead, fortunately,in Calcutta, it's business as usual.

After the story about the clinics, Hari finally broaches the economic part: the kidney from him costs around 2.000 euro, half down and half after the transplant. I try to do some bargaining, but he's adamant: "Sorry, fixed prices" and "for a Westerner it's rock bottom." Prakash, the adolescent son already destined for an explant in the near future, also intervenes. Taking his attention off the PC for a moment, he turns to me with brassy arrogance: "Listen, my dad's the best in the business: he makes a call to India and the transplant's done." In the end, Hari accepts only a redistribution of the installments: one third at a time like Krishna. And, again like Krishna, he also gives me an appointment for the next day to meet the donors and have them do the blood tests.

Out of jail with a kickback

If the meeting with Krishna had been filled with silences and tensions, negotiation with Hari proceeded, instead, in a much more direct way. Rather gross, perhaps, but completely without sentiment as required by any business transaction to conclude quickly, for the benefit of all concerned.

That night at dinner with a couple of Nepalese friends I ask about the two go-betweens I'd met during the day and discover they're well known in the city. Krishna Kalki ,my first contact , is a rising star in the sector: once Hari's pupil, he's now on his own, elbowing for his space in a fast growing market. He's never wanted to sell one of his kidneys directly, but he's had his assistant cum-watchman in India, Ashok, do it.

Hari Tamang, instead, is a veteran truly considered the number one in Katmandu with an average of ten clients a month. With net profits of 1,000 euro each, his monthly take-home pay is quickly calculated. Hari's men make the rounds of the city every morning ,sometimes also reconnoitering Katmandu's valley outskirts , looking for new youngsters to cut open. Hari's also had his problems with the law: three years ago he had a fight with a donor ,apparently over an unpaid percentage , and the latter reported him. He wound up in jail but seven months later, after paying a fine and adding a cut for the judge, he was out again. Afterwards, he reopened his business and at today its going full speed ahead.

The purchase of Deepak

At the store the next day, Hari demonstrates his efficiency by having three donors in my blood group located in less than 24 hours show up within a few minutes. They saunter into the alley alongside one another and, at Hari's request, introduce themselves to their European buyer like disciplined students.

One, called Dinesh, is 24 and comes from the southern Nepalese city of Hetuada. He says he married at 13 , now has three children and that his 35 euro a month carpet factory wage isn't enough to support them. The second, Bikran, 22, wearing a baseball cap and a Kurt Cobain T-shirt, sips a Fanta and says merely that he comes from Terai and needs money.

The third and youngest, called Deepak Lama, has a clean and timid face and seems well groomed even though his shirt is little more than a rag. Born in the Hetuada region's village of Terai, he explains that he comes from a family of "sukumbashi" , a Nepalese term that could be translated as "refugees," but here indicates people unable to afford even grass huts, who therefore sleep in the streets.

Deepak works in the same carpet factory as Dinesh ,which becomes a pretext for agent to sing the praises of his merchandise: "All three of them are of Lama stock like mine. Sturdy people, healthy bodies, which is why they're hired by the carpet factories. Believe me, they're the best donors , take my word for it; I'm an expert."

Then Hari, in a good mood, leaves the store and hails a cab to take us all to the Siddharta hospital for the exams. I have to wait at a curbside bar while he goes in with the boys. Half an hour later he reappears bringing the receipts for his immediate reimbursement. He points to the needle punctures on the donors' arms showing they've really taken the samples and then gives me an appointment for that afternoon , at his photocopy store as usual, when he'll have the results.

Punctually, a few hours later in the Bagh Bazar alleyway, the test results arrive. The first youngster, Dinesh, has a few irregular readings. "You can see he doesn't eat well", sentences Hari. In a few months he'll be ready for another client, but for now he's out of the picture. Biktan , the tight-lipped one,, is hopeless: "He's got kidney stones, might as well send him back to the village, here he'll only waste our time." As luck would have it, Deepak, the smallest boy, is OK on all counts: blood, kidneys, liver HIV, TB, hepatitis, and so on. " Therefore," says Hari, "you can take him away right now - after making the agreed 30% 700 euro down payment, of course."

Then and there I'm rather surprised: I hadn't thought things would have been concluded so quickly. Take him with me? Where? To do what? Hari smiles, almost good naturedly: "From now on he's your son, no? Well, then you have to know each other, familiarize. Take him to the market and get him some clothes. Offer him a restaurant dinner, have him sleep at your hotel. In the meantime I prepare the documents and in a few days we'll all go to Kolkata. Look, instead of sending you my watchman, for once I'll accompany you in person; that way you'll see how fast and simple it all is. But, in return, you spread the word about me, OK? Let them know that in Katmandu the good Hari is ready to save the lives of those who need transplants..."Then the 'good Hari' extends his hand, and the wad of rupees I give him goes quickly into the drawer of the fake wood table.

Fifteen hours a day at the loom

Shortly afterwards I'm with Deepak at Katmandu's Hong Kong Bazaar, an outdoor market near the royal palace, trying to imagine what to buy him for the trip to Calcutta. He stares in wide-eyed silence at the merchandise. Sudarshan literally takes him by the hand, and he smiles in disbelief before every stall. I think he'll need a backpack for the trip and he enthusiastically chooses a false Diesel for 250 rupees - about 3 euro. It then dawns on me that actually he has nothing -really nothing- to put into it, and so we buy him trousers, shirts, socks, underwear, a toothbrush, a nail clipper, soap... At the counterfeit Nike stall -4 euro per pair- Deepak grasps the still-laced shoes and tries to put them on the way they are. We explain to him that he has to unlace them first, which prompts his embarassed smile: he's never worn anything but plastic thongs. We end the shopping with a digital watch as he can't read one with minute and hour hands- and a fake Gucci belt for 3 euro that a cobbler has to punch three new holes in for him. Deepak may be of sturdy Lama stock, but he's thin as a rail.

In the taxi that takes us to the hotel just outside the city, the boy looks around him bewildered, without a word. At the guest house he takes a shower and comes out of his room proud of his new clothes before accepting a drink -a Sprite, naturally- and sitting at a table in the garden of the Planet Bakhtapur Hotel to begin the donor-patient familiarization process so keenly desired by Hari.

Deepak left his village in a bus at 14, because he lived in the street there anyway. In the capital he quickly began working at the carpet factory, which is what he still does today at 19 -the age he claims, although he may really be much younger. He starts at the loom at 5:00 a.m. At 10 there's a half-hour break for food, after which he continues - with one more half-hour break in the afternoon - until 8:00 p.m. This goes on six days a week, from Sunday to Friday. Saturday's set aside for the life of luxury: you only work from 5 to 10 a.m., after which you're free to hang out with friends. Deepak earns 3,000 Nepalese rupees (35-40 euro) per month, but keeps little more than half: 1.300 are docked by the factory owner for his food (rice and lentils) and rent for a room without a bath shared with three others. With the rupees left over, Deepak buys something extra to eat or drink and calls home once a month from a public phone to a small store in the village. They contact his mother and he calls her back 10 minutes later. Obviously he's longingly nostalgic ("I haven't been home for three years") but thinks he'll never leave Katmandu again: "With the kidney money I'll open one of those little stores here that sell loose cigarettes, soap, shampoo and things like that. All I need is one square meter, I don't ask for more, just enough not to stay in front of a loom all day. If anything's left I'll send it to my mother so she can at least build herself a wooden shack and not have to sleep out in front of the temple anymore."

During the next two days - while Deepak remains in the hotel to watch TV - Hari prepares the promised documents in which the donor claims to be my son and an unknown local woman certifies that she's his mother, confirming my paternity. The first document that arrives - whether or not bearing all of the ministerial stamps - is frankly embarassing for its errors in English grammar and syntax. I mention this to Sudarshan and he laughs about it: "It's an advantage if it's full of blunders; Nepalese government documents are all like that. The Indians consider us illiterate to the point that if they see a document from here written in good English they think it's a fake." In the end, however, we agree that the errors are really too glaring (my birth date, '62, has become my age: 62 years; the word "son" has been confused with "husband, " etc., and so we ask Hari for a new edition. Slightly improved, it arrives the next day with the same stamps and on paper bearing the same letterhead. Perhaps miffed for having had his first certificate rejected, Hari adds three new versions for the false mother, with as many photos of women I had slept with in the '80s. In all versions the women confirm that the boy is our son and declare their agreement with his decision to donate a kidney. In the end we choose the certificate signed by a certain Seti Maya, the most credible in terms of resemblance to my donor.

Apollo Hospital, room No. 25

My friend Sudarshan comes to Kolkata along with Hari e Deepa: ostensibly to assist me during my convalescence, actually to manage a situation which at that point has become more delicate. To justify my condition as a kidney patient- both with Hari and with the doctors - I know I'll have to show frequent signs of fatigue: in fact I should already be under dialysis, and if I'm not, it's only because I want to return from Asia with my new kidney. I always walk slowly and sit as soon as I can, but the act is more difficult carried on full time in the presence of a middle man used to dealing with real patients. Having to dine together every night, I follow a real patient's diet of water, a few vegetables and white rice.

It's probably all superfluous, because Hari doesn't seem to suspect anything at all. To the contrary, he lets himself go with proud stories of his work: "I don't understand why this should be against the law; it's a shame" he says, and adding as he points to Deepak: "If he needs money and you need a new kidney, why can't you negotiate? Bah!" Later, over dessert, he takes the photo of a Buddhist monk less than 20 years old out of his pocket: "Look, this is my next patient. For the State he could die; I bring him here to India and he lives for another fifty years. So you tell me why it should be illegal!". And he goes on: "The truth is that I don't work for money, I work to make people happy. Look how content Deepak is, and think of how happy you'll be when you're back in Italy and instead of that white rice you can enjoy a wonderful pizza!" Finally he becomes pragmatic again: "But remember, when you're back home, talk about me to your friends! Who knows how many kidney patients you've met in the hospital..."

The next day, Friday, the moment's finally come to meet the surgeon. Hari leaves the hotel early in the morning and takes a cab to the Apollo Gleanagles - to meet the doctor in advance so that everything will go smoothly afterwards. He explains to me that his usual reference, Dr Mishra, is at a convention or something of the kind and can't see us that day, but our meeting has been assigned to his deputy, a certain Dr M.H. Raibagi. "Don't worry, I also know him very well and he's an excellent surgeon." After a few hours the call comes in: everything's ready; we can go.

Driving through the suffocating heat of Kolkata, we arrive at the Apollo Gleaneagles, a large modern hospital complex in cement, only a few blocks from the city's outskirts of cellophane and bamboo. Hari remains outside with Deepak : "If the doctor wants to see the donor right away, ring me on the cellphone or come pick him up here; for now it's better for us to stay here. I go in alone with Sudarshan.

Dr Raibagi receives clients in Room No. 25 of the nephrology ward on the ground floor. He's a middle-aged man in a white gown and tie, speaks fluent English and has a pleasant smile. I explain my situation briefly, feigning unawareness that he's already spoken with Hari. I tell him about my illness and the dialysis that I don't want to submit to as "in Italy my social life is very active, a marketing job that keeps me on the run all day between cabs and meetings, and being connected to a machine for hours would ruin my career."

He agrees with me: "You're right, dialysis gets in the way..." Asking no further questions, he concentrates exclusively on selling his product well: "Our average of success in kidney transplants is close to 99%. We have the best rejection crisis medicines, air conditioned private rooms with a second bed for the assistant." As for times, they aren't a problem: "Naturally we have to repeat the exams for you and the donor, but everything's over in three or four days. After that you'll only undergo one week of dialysis here with us, and you'll be ready for the transplant. After a convalescence of 15-20 days and you can go back home with your new kidney." The costs? Dr Raibagi has no false modesy: "Between the operation, clinical tests and hospitalization we're around 5,000 euro, all included. You only have to add charges for medicines that Indian hospitals don't give..."

After which, the surgeon finally asks to see the documents: my blood tests -those falsified at the computer before leaving Italy - and the donor's bogus certificates. He gives Hari's false papers a cursory glance and looks up at me reassuringly: "Everything's OK, we can admit you on Monday." After which he sighs: "Of course, if the boy were really your son the possibilities of success would be 100%..." At this point I'm the one who provokes him: "And, instead, if he wasn't my son?" Raibagi stares at me: "Well, in that case, I'd have to prescribe a slightly stronger rejection crisis therapy, but you'll see that everything will be fine just the same".

For him, the hypothesis that Deepak isn't my blood relative is no more than a technical obstacle, certainly not an ethical or legal impediment. Amazed at the absurd ease with which everything is happening, I try to imagine some possible problem. "What happens, though, if Deepaks's kidney isn't compatible? Can someone help me find another one here?" The doctor smiles again: "We'll cross that bridge when we come to it, but you'll see there won't be any need. In any event, we´ll arrange it."

As the meeting ends, Dr Raibagi also offers to examine me right away. I politely decline, claiming fatigue, heat, an overwhelming desire to get back to the hotel at once. It doesn't seem strange to him at all: "OK then, come in on Monday, whenever you want. Just go past the line and knock on my door. We'll begin the clinical tests right away and then we'll admit you."

Sudarshan and I leave the hospital slightly dazed. Hari isn't there, but he's left word for us to wait: he's gone for a moment to greet another doctor. Deepak, left alone, sips sugar cane juice in the sun. If I were really a patient, within ten days his kidney would be in my body. Instead, the time has come for me to close everything. After leaving Sudarshan with some money for Deepak, I get into a cab and disappear in the steaming chaos of Kolkata.

(17 maggio 2007)